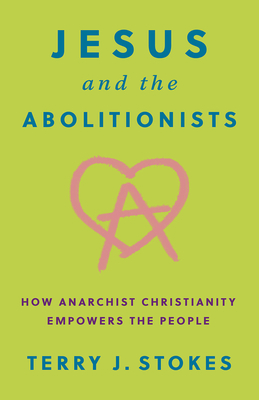

Book Review: Jesus and the Abolitionists: How Anarchist Christianity Empowers the People

Reviewed by:

Shaundale RenaAt first glance, I was drawn to Jesus and the Abolitionists: How Anarchist Christianity Empowers the People because of its eye-catching cover. I also didn’t know what to expect from the title, however, the word “Jesus” in big bold letters screamed “Pay attention!” So, I did. And while I will admit I needed to double-check “anarchist,” after I saw it (because I wanted to know how it related to Christianity in this sense), something just wouldn’t let me not choose this book. Turns out that while my mind was screaming politics, the pendulum swung in the opposite direction. Anarchism, as it relates to Christianity, simply means the abolition of government and systems. And while it can be considered political, this book is equal parts social and spiritual. Author Terry J. Stokes takes on the idea that while biblical principles should be used to build societies that allow people to support themselves in a community, church should not be used as a system to keep people bound by ideas and systems that suppress them. This book is quite thought-provoking, and the author radically and masterfully weaves two ideas together—one of religion and the other of rulership—with a skillful hand. He puts to good use his Master of Divinity and life experiences that span across ministry and philosophy. Surprisingly, the content is less religious and more relational; so, if you’re looking for a Bible Study, this is not it. Think more social studies.

After spending a day of reading, I accepted that perhaps this book chose me. I dove into Stokes’s work with a clean slate. I didn’t want whatever worldview I came with to taint whatever new information I was about to receive. I sat in a space of unknowing yet eager to learn. And learn, I did. One of the things I enjoyed about Jesus and the Abolitionists is that within its two parts that include ten chapters, it encompasses a unique blend of historical, biblical, logical and practical wisdom, as well as principles. Add doses of humor sprinkled throughout, and you will find a nice balance of ideology and personality as Stokes identifies what anarchism is and how it applies to a lifestyle where service to humanity is “an organizing principle for systematic theology.” In my favorite chapter, “God is a lover, not a ruler,” Stokes is neither legalistic nor dogmatic in his approach about God not using His power to yield a particular result. What struck me is his reference to Janelle Monáe’s statement that “God is nonbinary.” That and God does all He does out of love and not rulership or obligation—out of love and not out of authority. This was my aha moment: God is moving on behalf of people, not systems. In a subsequent chapter, the writer goes on to discuss principles of law—legalism. The thought that there’s only right or wrong, good or bad is where many problems lie.

Being open to embracing these new concepts of Anarchist Christianity allowed me to detach from the thoughts and patterns I have habitually lived where life is black or white (something he addresses), fighting off the occasional teetering of offense, and going where the writer took me—into the gray. My thinking floated. Let this be your warning: If you are a Christian who has never questioned God, the sovereignty of God, the existence of God, the power and/or the reign or intentions of God and just accepted the teachings of man, then this is likely not a good place to start unless you’re one of those people who simply likes to ruffle feathers in the name of Jesus.

However, if you’ve ever questioned God and have a deeper longing to know what’s not being taught in church on Sunday morning or during a Wednesday night Bible study, then this book is beckoning for you to read it with an open spirit and a willingness to see a different perspective on the very basis of Christianity: Jesus’s death, burial, and resurrection. In that case, carry on. The author makes it clear that the intent is to “demonstrate how reading Scripture in conversation with sound insights from history, literary studies, cultural studies, and ethics provides an interpretive lens through which to read it in a way that reveals reliable theological insights about God.” Stokes goes far as to say Jesus laying down His life is symbolic of dying to laws, as “Rulership ends when rulers have no one to rule.” And this is why I’m here.

As mentioned earlier, my thinking floated from chapter to chapter. I felt the tension surrounding what I label “spiritual bondage” leave my body as my inner self no longer resisted “being wrong.” There is a gray area, and Stokes craftily portrays it as he writes definitively with the ease of personal conviction, his tone reassuring and inspiring. My willingness to explore the ideas “God isn’t singular, God is neither or, and God is both and” was eye-opening. That tells me this book works. Because, in the grand scheme of life, God is absolutely, in fact, three composite entities. And, at bare minimum, we should all seek out nonviolent, nonmanipulative, and less controlling life alternatives.

Sitting with these thoughts caused me to relax. It was strangely freeing to not be confined, limited to a belief system—government, legal, spiritual or otherwise—to investigate the conversation forming in my head around Anarchist Christianity. I let my guard down and my conditions go. I felt part fear and part discomfort for even considering going along with what I was reading. My mind literally shifted. In fact, Stokes does a great job of drawing parallels between religion, relationship and rulership with the addition of Scriptures carefully chosen and strategically placed throughout. Jesus and the Abolitionists challenged me to change the language inside my head surrounding the Holy Trinity (God, Jesus, Holy Spirit) and rulership. The author uses words that are kind, gentle, and just as powerful as bigger, stronger, suppressive words. That alone was liberating! When we say Jesus is Lord, think Jesus is Love too.

If there is anything I would have liked to have seen less of, it would be half the footnotes. While they added subtle personality, I did find the footnotes made for a more textbook style reading experience. Aside from wishing there was a bibliography, Jesus and the Abolitionists is all for the journey to individual wellness, therefore community wholeness. If we ever get to a place where communities are self-sustaining and not dependent on the government, the byproduct is actual anarchism. And, as such, Stokes calls us to not just abolish some of the things we do to build a better society, but to abolish some of our thinking, too—like, finding ways for the community to still thrive even after the loss of a “head of household.” This is where the community steps in, as opposed to willfully leaving folks to struggle or simply figure it out themselves. There are many takeaways, such as autonomous community care and self-awareness, cooperative decision-making, and alternatives to government services. For me, self-awareness aligns with autonomous community care. Community provision trumps self-preservation, which is akin to starting a food pantry or growing a community garden in your literal own backyard.

Stokes is an associate pastor at a church in central New Jersey and the author of Prayers for the People, a collection of prayers that introduces Christians to the ancient practice of prayer-writing. He was a presenter at the 2020 Evolving Faith Conference, has written for the Episcopal Church’s Forward Day by Day publication, and is an editor for Earth & Altar magazine. In an email exchange, Stokes stated that he hopes readers would “come to understand that removing rulership from our conception of God can lead us to a more coherently liberating worldview, and that anarchy is the social structure that embodies all our highest ideals and hopes for the world.”

Stokes ends with a thank-you to readers that continues to challenge in the way of not just buying into the okie doke but to “try the Spirit, by the Spirit.” He carefully penned his appreciation and kept his task before him and his personality intact. Even though it’s hard to miss the intentional lowercase Christianity and Sunday, this book is well-written. Yet it was the right amount of risk taking, considering the subject. For Stokes, the intricacies of lowercase chapter titles worked well. It’s a win! His message calls for radicalized thinking; therefore, his method needed to break from the norm. And it did! I hope readers feel inspired to not just read Jesus and the Abolitionists but to put into practice some semblance of spiritual transformation for the overall good of the world.