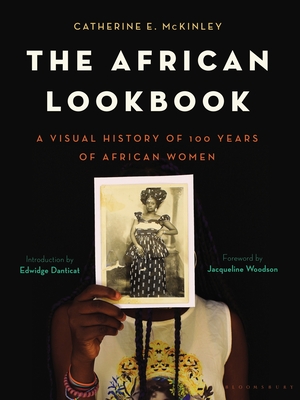

Book Review: The African Lookbook: A Visual History of 100 Years of African Women

by Catherine E. McKinley

Publication Date: Jan 19, 2021

List Price: $30.00

Format: Hardcover, 240 pages

Classification: Nonfiction

ISBN13: 9781620403532

Imprint: Bloomsbury Publishing

Publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing

Parent Company: Bloomsbury Publishing PLC

Read a Description of The African Lookbook: A Visual History of 100 Years of African Women

Book Reviewed by Robert Fleming

Identity and gender have always fascinated Catherine McKinley, one of the fewer 15,000 mixed-race children born in America during the 1960s and 1970s. They were adopted by white families before a rising tide of racial and political bias ended this trend. Ever curious about her past, McKinley was raised in a small, sanitized Massachusetts town where Black people, and images, were woefully absent. Now, she has continued her search for her identity with her new book, The African Lookbook: A Visual History Of 100 Years Of African Women. It is the final product of years of collecting historic photographs in an emotional and spiritual quest for a healthy sense of psychological wholeness.

“From an early age, images mattered to me, and gathering photos was a way to attend to the enormous aches I felt,” the author said. “They were a way of asserting an inheritance and belonging. When I went to boarding school in high school, I intended to free myself from the burden of social illegitimacy. I was free from the conspicuousness of my adoption. I began assembling vintage photos and discarded family I found in flea markets and bookshops on the dresser of my dorm room. I wrote a story of myself with each figure.”

While McKinley’s photo book is a rich visual feast (1870-1970), it serves to focus on the feminine beauty, cultural physicality, and innate resourcefulness of the African woman. The book is illustrated by artist Frida Orupabo, an Oslo-based Norwegian-Nigerian creator. Most importantly, the African woman is the mother of us Earthlings. She gave birth to all races, all cultures, all history of us on the planet. McKinley noted that her collecting of the photos of the women took on a life on its own, with friends and associates contributing prints of themselves. She added that the photos were a cherished keepsake which was close to her heart.

McKinley’s blend of word and image exposes the dominance of the major colonial studios, the twisted cultural myths and racial stereotypes, the overripe lust and desires of nudes in ethnographic postcards, and the awakening of the contemporary artistry of African photographers. What she notes is the abundance of detail found in every picture, especially the background, facial expressions, body language, apparel, and accessories.

During her research for the successful Indigo (2012), McKinley noted she had traveled through eleven West African countries, a journey for the discovery of the oldest indigo cloths, a tradition of various cultures, regions, and religions. She is an avid collector of photos along the key trade routes, touring some of the chief studios, gathering images to bolster her files.

Lighting. Film speed. Darkroom artistry. Subliminal messages. McKinley dismisses the controversial, hyper-sexualized images of the celebrated photographers of the modern age such as Helmut Newton, Guy Bourdin, Duane Michals, or Jeanloup Sieff. “You are aware of the spectre of violence,” she told a writer in 2020. “Some of these are among my favorite photos because of the beauty and the layered and contradictory narratives they contain. How do you reconcile the two? You don’t. For me, again, it’s all about what’s in the woman’s eyes – what she makes of it – it’s her ferocity or ambivalence, it’s raw pain, or how she implicates you – that leads me.”

Yes, the author realizes the concept of eliciting emotions by transforming reality and the present time. When followers of African culture think of the recent trend of the prints from the Motherland which made a splash in the 1990s with Seydou Keita and Malick Sidibe, it is not the whole story, not the entire canvas McKinley seeks to tell. Her goal is to tell the inner strength, cultural pride, political commitment, with a warm embrace of the power that comes with being a woman.

All of these pictures indeed tell a story. It’s as though some important events have just happened with each picture. According to McKinley, most of the photographs want to reveal each woman’s life through her regal body, through her defiant pose, through her distinct apparel. These women are very comfortable in their skins. In many cases, they refuse to concede, compromise, or surrender. For Black girls and women in this country and all over the globe, they have so much to be proud of.

Witness this magical, mythic photo album! Look at the lovely girl and the majestic women in the work of Seydou Keita, the Mali stylist. Check out the pair of hip kitties with dark glasses and cool garb by another Mali shutterbug Abdourahmane Sakaly. Dig the sleek hair-do of Eva from Ghana’s James Barnor. Take a gander at the tinted photos of the mysterious Dunau. Examine the solo and group figures of the Dakar and Saint-Louis Studios. View the fashionable Bondu girls by the Lisk-Carew brothers of Sierra Leone. And there are some stunning shots of girls and women from many African regions preserved for all time by many unknown cameramen.

In one of the most provocative sections of the book, “From the Colonial Peephole,” she celebrates dark skin in all of its glory. Although white men have sought to exploit the wondrous beauty and sexuality of African women for financial profit, the author shuns the realm of hard-edge fetishism and misplaced erotica. Without clothes, these women are a marvel to behold.

In the concluding segment on “Clothes For A New Nation,” McKinley sums up the aesthetic and political renaissance of African women during the years of rebellion and independence. “At the level of everyday lives, dress and camera were as powerful decolonizing agents as anything in the 1950s-1970s,” she writes. “African women, appearing in various ‘unfirms’ of statehood as they marched and paraded and performed Independence strivings, were redrawing the economy of power and identity in the social and political imagination… .Independence had opened a crossroads for identity, a loosening of strictures for many women, and an explosive optimism.”

In the introduction by acclaimed writer Edwidge Danticat, she writes: “Look, I have gathered these images, not just for me, but for you, and also for them, who have reframed and reclaimed the camera as their own.”

We must pay tribute to Catherine McKinley’s determined work in collecting and presenting these historic, dignified images of African women and their role in changing the cultural and political fortunes of our homeland. Never accept a substitute or a copy. This is the real thing. Men and women alike, we all stand on their broad shoulders.