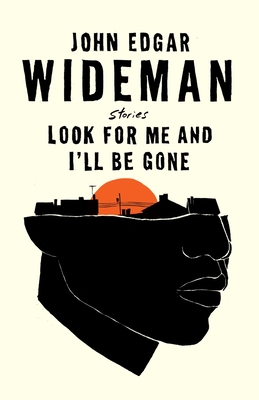

Book Review: Look for Me and I’ll Be Gone: Stories

by John Edgar Wideman

Publication Date: Nov 09, 2021

List Price: $26.00

Format: Hardcover, 336 pages

Classification: Fiction

ISBN13: 9781982148942

Imprint: Scribner

Publisher: Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Parent Company: KKR & Co. Inc.

Read a Description of Look for Me and I’ll Be Gone: Stories

Book Reviewed by Robert Fleming

Like Ishmael Reed, Clarence Major, and other legendary African-American male writers of their generation, John Edgar Wideman, at eighty, is nearing the twilight of his writing career. He, however, continues to produce work of the highest quality. Following the collected short fiction volume, The Stories of John Edgar Wideman (1992), consisting of 35 stories, the writer published three more story collections: God’s Gym (2205), Briefs (2010), and American Histories (2018). Currently, he adds another gem to his literary crown: Look For Me And I’ll Be Gone, another surprising grouping of his groundbreaking short stories.

A native of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Wideman, a professor emeritus at Brown University, has worked the controversial themes of family, race, trauma, personal freedom, love, and rage, through his revamped experimental prose. As a student-athlete at the University of Pennsylvania, he later was granted a Rhodes scholarship in 1963 as the second African American to attend Oxford University. In 1965, he studied for an MFA at the Iowa Writer’s Workshop under Kurt Vonnegut, among other teachers. In 1967, he published his first novel, A Glance Away, and eventually continued his art, creating nine novels, six collections of short stories, and five memoirs. He has earned most of the awards available to writers including the MacArthur Fellowship (1993), Prix Femina Etranger (2017), and the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction twice (1984, 1991), an honor granted only to three other writers: E. L. Doctorow, Philip Roth, and Ha Jin.

Wideman’s work has evolved from his usual subjects focusing on his family and friends in the Black community of Homewood, a neighborhood in Pittsburgh. Many of the stories in the Homewood trilogy (Damballah, Fever, All Stories Are True) form the foundation of the author’s writing, but now he concentrates on matters away from his former stomping ground. In his new collection, he blends fact and fiction in a heady mix of actual events, tragic figures, and shifting global events.

With his powerful tale, “George Floyd’s Story,” Wideman doesn’t recreate the shocking act of a white policeman’s foot on the black man’s neck but rather than he moves beyond the racial insult to the emotions we felt upon seeing the hateful act.

Wideman the all-seeing sage writes:

I will not pretend to bring GF to life. Nor pretend to bring life to him. GF gone for good. Won’t return. No place for GF except the past. And past not even past, a wise man once declared. Same abyss behind and in front of us is what the wisecracker writer signifying, I believe, and if I truly believe what he believed, where would I situate GF if presented an opportunity to put him somewhere him alive. Not here. Not here in this story where I know better.

One thing still haunts Wideman. When he was married to his first wife, Judith Ann Goldman, an attorney, they were parents to three children. In 1986, Jacob Wideman, his son, was convicted of murder while he was a minor and sentenced to life in prison without parole. All appeals failed. Wideman had been witness to a previous criminal situation where his younger brother, Robert, was charged for second-degree murder in 1975 with two men during a robbery. He was also found guilty and sentenced to life. Whether writing about justice or its defects, the author sometimes serves up a cautionary tale or a parable or a surprise of myth-making. However, he always compels the readers to use all of their senses and imagination.

There is the topic of the loss of personal freedom which riles him. It has been a theme that has repeatedly appeared in his books, especially in his story, “Penn Station:”

Prison strips away time. Leaves your body bare, bones shivering. No end or beginning to prison time, my brother schooled me. Time shrivels to routine, repetition. Time inverted. Longer a sentence, less time mattered. Prisoners own no time. No time belongs to them.

This book, published forty years after his first collection, requires a unique knowledge of the Wideman literary code, absorbing the words and images in a turning-and-twisting mesh-up of narrative, and a suspension of the reader in time and space. Like most of the jazz and blues greats, he employs the oral tradition to full effect, giving tribute to the idioms popularized in Albert Murray’s seminal Stomping The Blues (1977). Or like the free jazz mavens Coltrane, Rollins, or Dolphy, he gives the readers “sheets of sound,” irregular tempos, odd tones, or bizarre chord changes. This is the Wideman code.

Wideman understands the negative penalties existing among the unfortunate, psychological stress, emotional trauma, violent outcomes, and the demands of black manhood. He leaps over rigid slogans and strict dogma to experience the real-life consequences. He doesn’t bite his tongue. He doesn’t shrink away from his role as an unbiased observer.

In an endless riff in his tale, Ipso Facto, he ponders:

Why kill kids, young man, babies even, why kill anybody any age standing around a street corner, sitting on a stoop, in a playground, in an alley, the poolroom, at a party or a funeral or picnic, or strolling your sis or mom’s block or enemies, your competitors way over crosstown on the south side or north side who would need to be gunned down. Is shooting and killing a duty, thrill pleasure, crime, fate, penance.

A highlight, “Arizona,” which appeared in the New Yorker, is a letter to soul-crooner Freddie Jackson, whose song, “You Are My Lady,” provides a musical background in a car containing the writer’s son and legal team going to a state prison. “I’m moved by your song’s power to free my son,” he writes. “Not exactly envious, but more than desperate to figure out how you do what you do. Did once in a car on an Arizona highway and why not again. I want to learn to emulate your example. Rescue him.”

Of the 21 tidbits gathered between these pages, his story, “Rwanda,” moves between a mournful sense of guilt and regret over tribal cruelty to the possibility of redemption in the Motherland and domestically. “He writes: “Why Rwanda. Because the horrors, sweet girl, unleashed in Rwanda, expose the stakes, the power, and chaos, that the thought experiment confronts. Rwanda a country whose authorities announced the end of the world coming immediately…Hurry, hurry the government said. Not a moment to spare.”

There will be more literal jewels coming from John Edgar Wideman. He once said good writing is always about things that are important to you, things that are scary to you, things that eat you up. For readers of the Black experience, we need to hear more from our elders and their wisdom. Alas, Mr. Wideman, continues to amaze and astonish us.